Textile Industry Impact Calculator

This calculator estimates the economic impact of Jamsetji Tata's textile model versus British industrial approaches in early 1900s India. Enter values based on the 1907 Tata Mill in Nagpur to see how Indian-owned production differed from British models.

Your Production Results

Your Production Costs

Total Machinery Investment: $110,000

Monthly Labor Costs: $60,000

Monthly Raw Material Costs: $750,000

Total Monthly Costs: $820,000

Your Production Revenue

Monthly Revenue: $3,750,000

Monthly Profit: $2,930,000

Profit Margin: 78.16%

Tata Model vs. British Model Comparison

Tata Model (Indian Owned)

Capital Source: Domestic Indian savings and investors

Workforce: Local Indian labor trained on-site

Profit Flow: All profits remain in India

Market Focus: Medium-weight yarn for domestic & export markets

British Model (1900s)

Capital Source: British banks and overseas capital

Workforce: Skilled British workers

Profit Flow: Profits sent back to Britain

Market Focus: Fine yarn for high-end British textiles

Key Insight: The Tata Model's success came from vertical integration and domestic capital investment, allowing profits to stay in India rather than flowing to British shareholders. This created a self-sustaining economic ecosystem that fueled India's industrial growth.

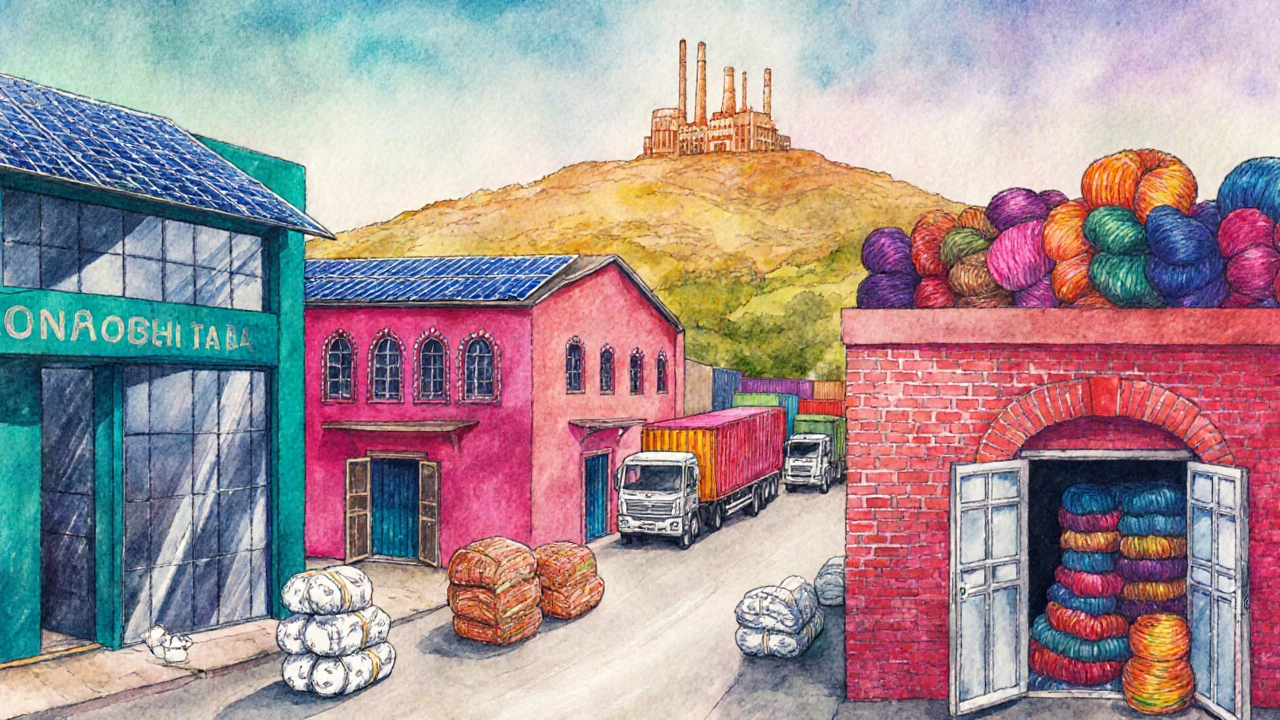

When people think of the Indian textile boom, the name that most often comes up is Jamsetji Tata. He didn’t just start a single mill; he sparked an entire ecosystem that turned India from a raw‑cotton exporter into a global fabric producer. This article breaks down who he was, why his work matters today, and how his legacy still shapes the sector.

Who Was Jamsetji Tata?

Jamsetji Tata was a 19th‑century Indian entrepreneur born in 1839 in Navsari, Gujarat. He founded the Tata Group, which today spans steel, automotive, hospitality, and of course textiles. His vision was simple: build Indian‑owned factories that could compete with British imports.

Educated in Bombay and later exposed to industrial practices in England, Tata returned home with a plan to create a self‑sufficient textile hub. He believed in “Swadeshi” - using Indian resources and talent - long before the movement gained political momentum.

Why Is He Called the Father of the Indian Textile Industry?

Before Tata’s entry, the cotton‑spinning landscape was dominated by British firms such as the Bombay Spinning and Weaving Company (1854). Indian workers were mostly employed in handloom villages, and the country exported raw cotton rather than finished cloth.

In 1907 Tata launched the Tata Mill in Nagpur, Maharashtra. It was the first major cotton‑spinning and weaving plant owned by an Indian. The mill used state‑of‑the‑art British machinery, but all capital, management, and profits stayed in Indian hands.

His focus on vertical integration - owning everything from raw cotton procurement to finishing - set a blueprint that later Indian entrepreneurs copied. The result was a rapid rise in domestic textile output, a decline in dependence on British imports, and the birth of a new industrial class.

Key Milestones in Tata’s Textile Journey

- 1881 - Established Tata Iron and Steel Co., laying the financial foundation for future textile ventures.

- 1897 - Formed the Tata Manufacturing Company, which later spun off into the textile division.

- 1907 - Opened Tata Mill in Nagpur, equipped with 55,000 spindles and 6,000 looms.

- 1910 - Introduced the first Indian‑made synthetic dye, reducing reliance on British chemicals.

- 1915 - After his death, his son SirRatanTata expanded the mill network to Surat and Kolkata.

Impact on Regional Textile Hubs

The success of Tata Mill turned Nagpur into a “Cotton Capital” of central India. Within a decade, nearby towns set up their own spinning houses, creating a cluster effect. Surat, already a silk and later a synthetic fabric center, borrowed Tata’s vertical‑integration model to become the world’s largest garment‑export city.

Today's textile corridors in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and TamilNadu all trace part of their industrial DNA back to Jamsetji’s approach: invest in modern machinery, nurture local talent, and keep profits within the country.

Comparing Tata’s Mill with Contemporary British Mills

| Aspect | Tata Mill (India) | British Mill (England) |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Indian entrepreneurs (Tata Group) | British shareholders |

| Capital source | Domestic savings & Indian investors | British banks & overseas capital |

| Workforce | Local Indian labor, trained on‑site | Skilled British workers |

| Product focus | Medium‑weight cotton yarn for domestic & export markets | Fine yarn for high‑end British textiles |

| Technology | Imported British machinery, locally maintained | Cutting‑edge British machinery |

Other Pioneers Influenced by Tata

While Jamsetji Tata laid the groundwork, several contemporaries accelerated growth:

- SirRatanTata - expanded the mill network and introduced synthetic fibers.

- MadhavSingh - founded the first Marwari‑owned textile conglomerate in Delhi.

- SirC.P.RamaswamiIyer - championed textile education, establishing the Government College of Textile Engineering in 1915.

These figures borrowed Tata’s emphasis on local capital, technology transfer, and market diversification.

Legacy in Today’s Textile Landscape

Modern Indian textile exports hit $44billion in FY2024, up 12% from the previous year. A large chunk of that growth stems from the integrated supply chains first demonstrated by Tata’s mill. Moreover, the Make in India initiative mirrors his Swadeshi philosophy: promote indigenous manufacturing, reduce import dependence, and create skilled jobs.

Companies like Arvind Limited and Reliance Textiles still cite Tata’s model when they talk about vertical integration and long‑term investment in R&D.

Common Misconceptions

- It wasn’t the first cotton mill in India. British firms set up earlier mills; Tata’s claim is being the first large‑scale, Indian‑owned enterprise.

- He didn’t work alone. A core team of engineers, financiers, and British machinery agents helped turn the vision into reality.

- His impact was limited to textiles. The profits from the mills funded Tata’s later ventures into steel (Tata Iron and Steel Company) and hydroelectric power.

Quick Takeaways

- Jamsetji Tata (1839‑1904) is widely recognized as the father of the Indian textile industry.

- His Tata Mill in Nagpur (1907) was the first major Indian‑owned cotton‑spinning and weaving plant.

- The mill introduced vertical integration, domestic capital investment, and technology transfer-principles still used today.

- His legacy lives on through modern textile hubs, government policies, and global export figures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Jamsetji Tata called the father of Indian textiles?

He founded the first large‑scale, Indian‑owned cotton mill (Tata Mill, Nagpur, 1907) and introduced a business model that integrated raw cotton sourcing, spinning, weaving, and finishing-all under Indian control. This broke the British monopoly and set the template for future Indian textile entrepreneurs.

What were the main innovations introduced by Tata’s mill?

Vertical integration, use of imported British machinery maintained locally, and the establishment of a training program for Indian engineers and operatives. He also pioneered the use of Indian‑produced synthetic dyes by 1910.

How did Tata’s textile ventures influence other Indian industries?

Profits from the mills funded Tata’s entry into steel (Tata Iron and Steel Company) and later power generation. The same integration model was copied by steel, chemicals, and automotive sectors, accelerating India’s overall industrialization.

Are there any modern companies that still follow Tata’s model?

Yes. Arvind Limited, Reliance Textiles, and the current Tata Group’s textile arm continue to control the entire supply chain-from cotton farming to finished garments-mirroring the vertical integration Tata pioneered.

Did the British oppose Tata’s mill?

Initially, British traders saw it as competition, but Tata’s ability to purchase machinery from Britain and employ local labor eased tensions. Over time, the mill became a supplier to British textile firms, turning rivalry into partnership.